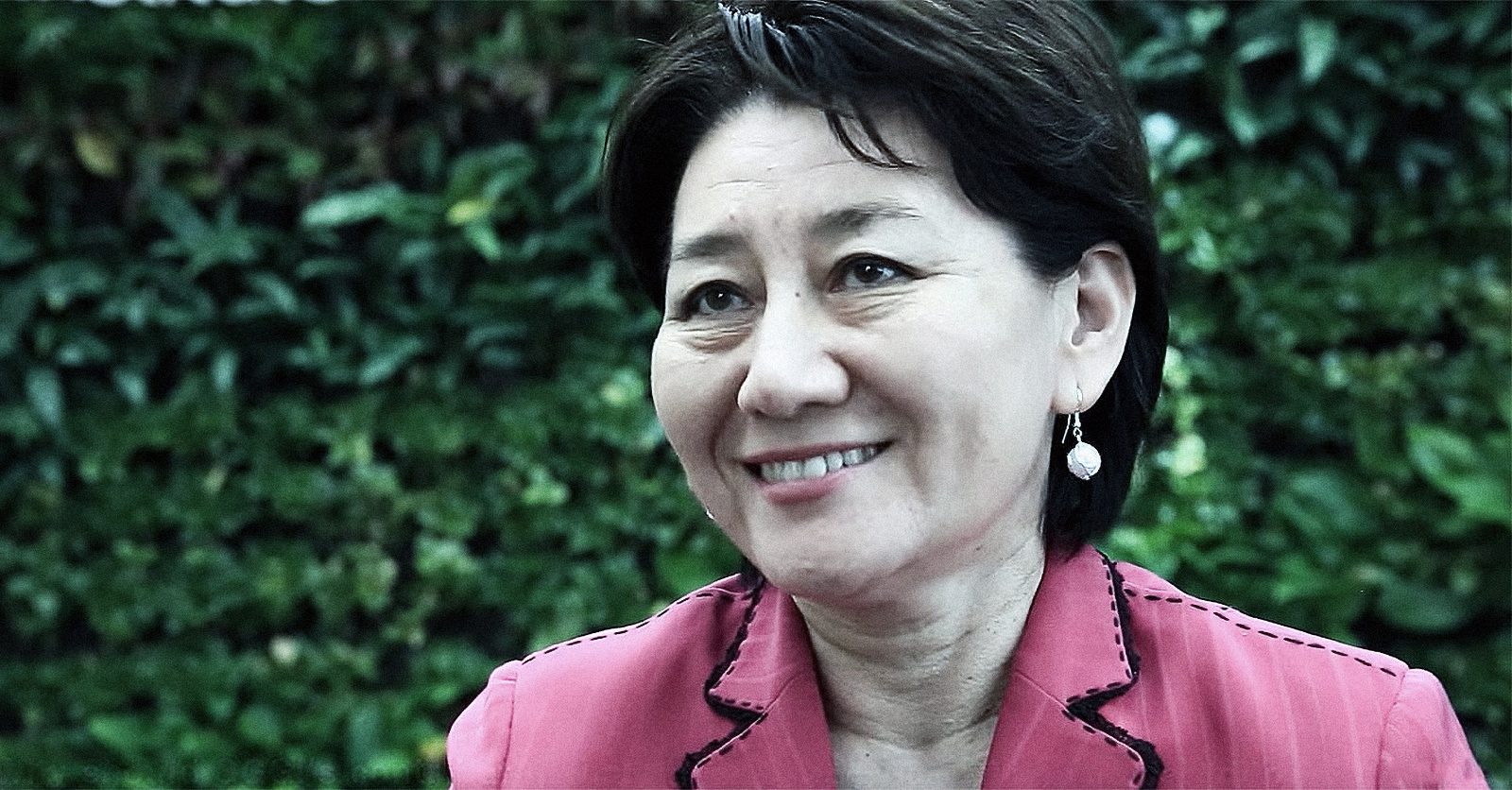

Fauziya Ali is the Founder and President of Women in International Security Horn of Africa and Sisters Without Borders, a network of women leaders championing peace and security in their communities and country. In a recent wide-ranging conversation about peace, leadership and COVID, she drew a line through the issues of domestic and gender-based violence (GBV), poverty, violent extremism and gender equality.

When asked about the impact of COVID-19 on her work, Ali spoke about the “silent killer’ of GBV: “We noticed that in the first few months [of COVID] in Kenya it went up 42%. Later, in a few months, it went up 50%. It was really a concern for us. We started engaging with people right away so that there was greater awareness about it.” But increases in GBV weren’t random; lockdown restrictions and the loss of income led to increased stress levels. Moreover, many of the public health guidelines were unsuitable for those living in the Nairobi slums, as instructions to wash hands and wear masks were impossible to follow.

Ali and her colleagues thought creatively about the multitude of problems and sought to address them collectively. First, they raised awareness that GBV is wrong. Second, they distributed information about services, and created a program where those experiencing violence could gather to create masks and sell them in their communities. This helped with their mental health. Third, they worked with households, “preaching peace.” “Because even when there is an absence of gender-based violence, peace begins from the house.”

This network used the radio and public art to share important information, since many households don’t have access to phones and the internet. They also worked with young, women graffiti artists to put out information about access to services and how to protect themselves from COVID.

In the longer-term, Ali used her network to inform elected officials about the growing levels of GBV. “The Chief Justice at the time was so shocked.” But in response to hearing this information, the government took several key steps supporting hotlines and reopening courts online for GBV matters. Ali also worked with local chiefs, holding meetings outside and informing them about the challenges and how they needed to work together to address GBV in local communities. She made sure they were aware about the hotline and other services.

“But what COVID did was really showcase the inequalities we have in our communities,” Ali said. Gender-based violence existed in these places before the pandemic, but people weren’t talking about it or taking it seriously. People didn’t like the “optics” of it or found it hard to get financing for programs. COVID changed that.

COVID also impacted the work Ali does to prevent and respond to violent extremism. So much of that work takes place in person and had to be curtailed: “There was a reduction in interventions because for us, most of the interventions are face-to-face, engaging directly with communities, doing community awareness, doing a lot of dialogues, building trust between the security sector and communities and vice versa … Within the first few months we had to … move more online to have some of the activities.” They also met outside and used sport to keep the interactions going.

While every individual takes his or her own path to becoming a violent extremist, Ali works to create dialogue between community members and security actors: “When you look at violent extremism interventions, towards prevention or countering it, it is very state-centric sometimes and it is very militarized and securitized. And the challenge with that is that it kind of closed off communities from participating in interventions. There is a really large gap between communities and security actors.” There is also a lot of distrust between the groups. Officers often live in the communities but are not seen as part of it. “Police officers are not even seen as human beings.”

Conversations are important. “At the end of the day having to open up, each party sharing and opening up about where their challenges are, and what they want to see as a change, and then both sides are starting to work.” After these conversations, “You have a community member standing up and saying, ‘I finally understand what a police officer’s life is like and they are a part of our community.’”

She also connects communities to elected officials so that elected officials have a better sense of what is happening on the ground. She brings small groups of 20-30 community members together to speak with their representative so that the official hears firsthand about the issues that the communities are facing and what is attracting those that are joining violent extremist organizations. Sometimes it is a social issue that drives distrust. Recalling one event, Ali said, “One of the women told the women representative, ‘Our children want to go to school, but we cannot afford to take them to school. We need these scholarships that have been provided. These should get to the needy people. And the needy people is us.’ And so she heard that and she said ‘Wow. I will make sure that some in this community get some of these scholarships (that are issued out from her office).’”

The Sisters Without Borders network is key to this work. The network is predominantly made up of women-led civil society or faith-based organizations, with few male members. They’ve been actively pulling in young men who champion the women, peace and security agenda. “The primary purpose was for that knowledge sharing to keep happening and for us to stay connected. For most people, even if you talk to members of the network, it’s not a project for us, it’s a way of living. We need to continue to have discussions. We need to continue to have influence collectively. “One of the programs is called BRACE – Building Resilient, Active Communities of Empowered Women – focused in Western Kenya. Ali explained, “We work within the school system to ensure that at a very young age, discussions around gender, women and empowerment, inequity, etc., are taking place, but they’re seeing a male, a young person, championing this, talking to them about this, defining the concepts, supporting the development of what we call peace clubs in the community. It’s important that they see these faces.”

What makes Fauziya such a good leader? Her passion for her work is evident in her face and words. But in her mind, she is successful because she is a “quiet leader.” “We are sometimes in the room, and everyone is putting their point across and they’re sharing. Coming from an African context, we’re story-tellers, we are charismatic, but by virtue of being a quiet one, you listen more, and you are able to open yourself up to the different perspectives that are in the room.” That helps her to co-create programs. “The beauty of co-creation is that it helps with really contextualizing the interventions. You’re sharing, yes, this is what our values are and what our intentions are, but the communities are driving it. ‘You design based on your context and we will come, and support and you will come on our side as well and support.’ I think that’s the beauty of co-creation in a network as opposed to consultation.”

go back: about

go back: about