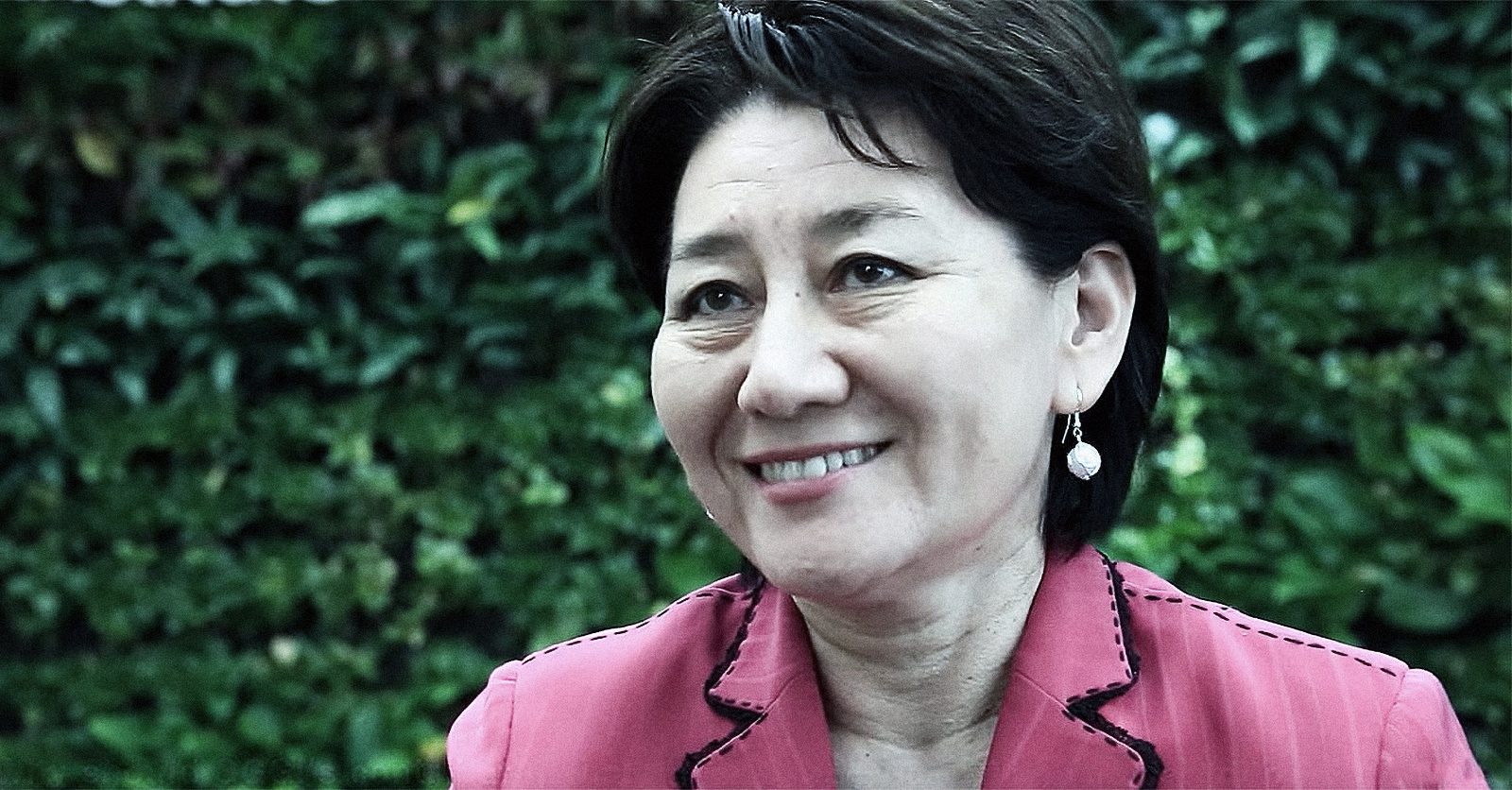

Miriam Lexmann took her seat in the European Parliament in 2020, representing Slovakia. COVID was emerging as a global health crisis, and that “made my start in the European Parliament very difficult,” she said in a recent interview. “We were delivering policies to combat the crisis and safeguard the main areas where the EU should be strong, but the situation wasn’t easy because we were [also establishing] a new style of working.”

When asked about lessons she has learned, she is quick to point out the importance of clear and trustworthy communications. “One of the lessons is that in a democracy it is vital that citizens have enough information and the information is not contradictory. When people are confused, when they don’t know what is happening or feel they don’t have all the information, they become vulnerable to disinformation and manipulation.” She noted that both the EU and Member States, including her native Slovakia, were sometimes late with policies and were not fully prepared to answer citizens’ questions.

Disinformation, especially online, has been rampant during the COVID pandemic. As Lexmann said, “If citizens don’t get information from the government, they will get it from other sources, which creates a distrust of government. Then it is very difficult to lead the country out of a crisis because people start to believe untrue information, sometimes on social media. People start to believe and trust these sources and then they compare it to information from the government. This can turn them against the government.” And she notes the current increase in disinformation is not limited to this health crisis: “Today, information doesn’t have borders. On social media, information is spreading across the borders, across different languages. That is why democracies [must deal] with this challenge which is undermining the pillars of the free world.”

Within the European Parliament, Lexmann is a Member of the Committee on Foreign Affairs. When asked whether the committee had previously thought of a global health crisis as a foreign policy or security issue, she responded, “We knew that there were hybrid means used by totalitarian or autocratic regimes which are undermining our democracies, but we did not think that health might be one of them.” Expanding on this idea, she said, “One of the lessons that we have learned in a hard way is that health can be used as a means of global competition or threat. Another issue we have learned is that economic dependency (particularly on China) can also be a threat and … used as a coercive means to put pressure on member states.”

In the EU, medical supplies and some medicines were difficult to obtain early in the pandemic, and that also increased awareness of dependence on China for these products. As Lexmann said. “ We could have expected this and I believe that the democratic world should have been more ready and should have realized that this dependency can turn against us and can become a threat.”

Lexmann thinks broadly about the relationship of European Parliament member states with the totalitarian and autocratic regimes. “I believe that we should be following our values, written clearly in European Union treaties…I believe we have failed in bringing these values into our foreign policy actions.”

She connects economic dependency with human rights. “I think that we need to come back to the basic values and we can navigate out of this problem. [I am concerned] that we have been blindly deepening more and more trade cooperation with China, which is one of the worst communist regimes — which stands against human dignity and human freedoms, violating human rights.” For example, trade relationships and other forms of cooperation give some countries political cover. “We are starting to become morally ‘co-responsible’ for the regime because economic cooperation brings wins for China.” Lexmann said. “The regimes have learned how to use this economic cooperation not only to strengthen its power back home, but to undermine our democracies … We should have realized much earlier that today’s totalitarian regimes have learned how to use economic cooperation with us to strengthen their own power and undermine our democracies, through corruption and disinformation, through manipulation of public opinion.”

In thinking about gender issues, women’s civil society organizations or her leadership style, Lexmann demurs. While the role of “traditional” civil society organizations is important, she thinks governments must think bigger with regard to both individual citizens online and other actors such as businesses, the private sector, and church organizations. “I believe it is absolutely important that we build something from the bottom up, and that we create [a political infrastructure] that will help the people and the civil society and the political leaders and businesses and private sector [come together and] heal the society from the bottom.”

Lexmann talks about the important role of her family in her development as a leader. “I come from a very big family, and I come from a former dissident family. I grew up in communist Czechoslovakia as a child. And I think this has impacted my leadership style.” Continuing, “We face many challenges and I believe the people from the ex-Communist countries who encountered totalitarian regimes, we are more sensitive to the ways how our freedom and democracy are being challenged. I try to bring this into my leadership and point out those issues.”

She closes the interview bringing together her ideas about communication, values and democracy saying, “The combination of the past, my country, my childhood and my work with the International Republican Institute is a strong navigation in my leadership which I help will safeguard our freedom and will help those who still fight for freedom in their very, very difficult fight.”

go back: about

go back: about