Established in 1949, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) guarantees the freedom and security of its thirty member states through political and military means. Central to NATO is Article 5 of the treaty establishing the organization, in which members agreed that “an armed attack against one or more of them… shall be considered an attack against them all” and that following such an attack, each Ally would take “such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force” in response. Significantly, Articles 2 and 3 of the Treaty had important purposes not immediately germane to the threat of attack. Article 3 laid the foundation for cooperation in military preparedness between the Allies, and Article 2 allowed leeway to engage in non-military cooperation. In early 2020, COVID-19 caused the multilateral organization and its member states to respond to a new kind of threat.

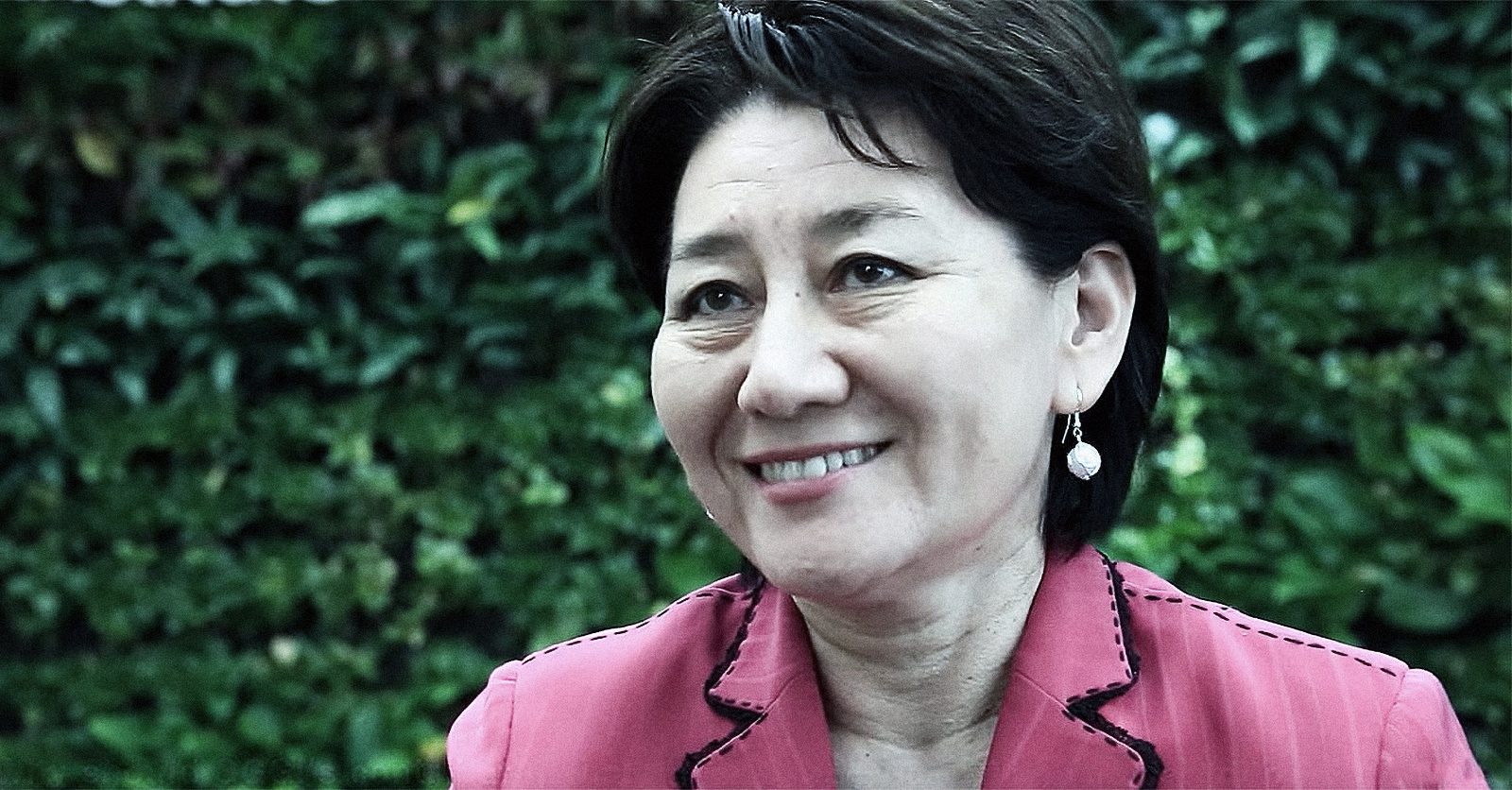

Radoslava Stefanova became the Head of the Integrated Air and Missile Defence Section in NATO’s Defence Investment Division in September 2000. She spoke recently about NATO’s response to the global pandemic and the organization’s effectiveness more broadly.

“The organization as a whole reacted very well to the challenges that were posed by the pandemic. What NATO did in addressing COVID was to use its capabilities — specifically related to rapid air mobility — to move troops, equipment and other relevant materials for use through the pandemic,” she said. “We had to also make sure that the core mission of NATO — defense and deterrence of our nations — remained intact and able to step up to the challenge of the pandemic.”

When asked about the past year and half, Stefanova shared that the pandemic impacted NATO in big and small ways: “The things that we took for granted before — going to the office, meeting in person, making decisions in meetings — all of that had to be repurposed so that we did not endanger our staff or our troops. It took some adjustment as we went along, but we were able to establish a way to do our work without putting anyone at risk, and do it quickly.”

The pandemic also expanded how the security of member states was defined. “The pandemic also touched the core of security for our members. The fact that we were able to use our capabilities to address the specific need to ship supplies, oxygen, respirators, all of that showed the importance of NATO. We were able to show that we don’t only transport troops but needed medical supplies because we have the equipment and capacity.”

In June 2021, following a NATO meeting, an official communique issued by the Heads of State and Government reiterated their commitment to maintaining “an appropriate mix of nuclear, conventional and missile defence capabilities for deterrence and defence.” In her position, Stefanova leads the Integrated Air and Missile Defence Section. “It is an interesting and demanding job,” she says. “I am enjoying myself, and learning a lot because I only transferred to this position a little over a year ago. Before that I was head of the Russia/Ukraine desk in the political affairs division which was another challenging aspect of what NATO deals with. It is a learning process for me going forward, ”

Asked about how her previous academic career and policy experience shapes her perspectives, Stefanova says “I do come from an academic think tank background, which was fundamental in helping me understand the grand picture in terms of defense and deterrence, and the evolution of concepts and the significance of NATO and ensuring the security of our members. The academic portion was very important in the formation of my thinking.”

So, why leave academia? “There came a point where I had to ‘pick a side’.” Stefanova explains. “It was extremely rewarding when I started at NATO — I would write something and I would hear the decision makers say it, and then others would agree and it would be implemented. It was unbelievable to me that I could do this.”

Unlike most other organizations, NATO operates by consensus. “NATO’s biggest strength is the power of its consensus. We have thirty members and they don’t agree on all policies.Their views need to come together somehow, which is the result of long and at times frustrating committee work. But when that work is done, what comes with it is legitimacy and strength of a policy agreed to by thirty nations. Agreed language at NATO is almost sacred and not to be touched.”

So, where does the political will come from? “At NATO, you have 30 nations that are very like minded, although they may not have the same identical national interest and views on defence and security. But to join they have had to meet certain standards and keep them up. These are countries that have come closer together by definition of being NATO members. Nevertheless sometimes the debates in these committee settings – where we strive for consensus – can be quite long and not always easy but we start with the knowledge that the members don’t disagree fundamentally on the overall objective. The devil is sometimes in the details and where these debates come harder. The role of the international secretariat is to foster this consensus and find the common points and bring them closer together so that we have a final product. There is a lot of negotiation and mediation in the process. I am quite passionate about this and it is at the core of what we do. When it’s finished its weight is bigger and more important. It’s hard to argue with something that thirty nations have endorsed.”

Stefanova isn’t sure if being a woman has influenced the policies she has proposed or her leadership style. She says, “It is an interesting and demanding job. You are right that it is male dominated, more so than my previous position. I am learning to cope with that, but I like a challenge.” However, “I am not sure whether the fact that I am a woman has determined how I have handled certain things or how I turned out as a person. I am not quite sure how to draw the difference. I continue to see challenges in asserting myself in a male dominated world, but it is my personality that has helped me along the way.”

When discussing NATO’s commitment to the women, peace and security agenda, she notes that NATO recognizes the disproportionate impact that conflict has on women and girls, the vital roles women play in peace and security, and the importance of incorporating gender perspectives in all that NATO does. As she says, “NATO is evolving in terms of its commitment to women in peace and security and ensuring a gender perspective. In my 18 years here, I have seen continued positive evolution in this sense.” In addition, “We are also trying to mainstream the gender perspective into everything we do, hire gender advisors, and ensure that there is freedom of expression and that women are heard as much as men.”

Stefanova goes on, “We take this very seriously — all of our members and the Secretary General himself are adamant about making progress by working with partner nations and other organizations to advance that agenda.”

go back: about

go back: about